How Iconography saved Art during the Scottish Iconoclasm – a thought piece

1

1

“We have to ask ourselves whether or not the symbolical significance of a given motif is a matter of established representational tradition . . .; whether or not a symbolical interpretation can be justified by definite texts or agrees with ideas demonstrably alive in the period”2

Introduction

This essay seeks to demonstrate that an iconographic approach alone is inadequate when considering Northern Renaissance art. The premise will be explored by considering how the iconographic motifs were perceived at the time, in the context of society and how such perceptions changed over time.

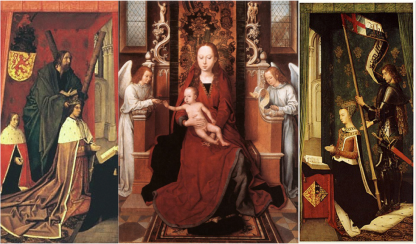

All of this will be explored with reference to Hugo van der Goes’ ‘Trinity Panels’. This is a wholly theoretical exercise because there is no evidence to explain the patron or donor’s intentions or the disposition of the panels during the 16th century3.

Changes in the perception of the panels’ iconography may provide a key to their survival. The iconoclasts were not indiscriminant vandals; they vented their spleen on devotional objects viewed as ‘graven idols’ contravening the Second Commandment. Objects which had cultural/political significance, did not offend, were of use or, more importantly, could not be used for veneration survived e.g. stain glass windows.

In this essay it is not intended to review the numerous theories regarding whether Hugo van der Goes painted all the panels, where they were painted, whether or not the patron travelled to the Netherlands to be painted etc. This is simply a matter of expediency as the length of this paper does not afford such an indulgence.

The Outer Panels

The four surviving panels will be considered in turn, starting with those visible when the triptych was closed.

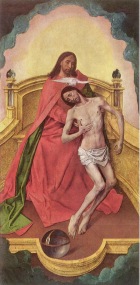

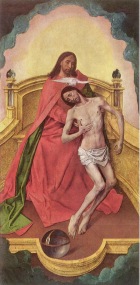

The Trinity Panel

This depiction is what Panofsky entitled as a ‘Trinity of the Broken Body’4. Christ’s body is realistically rendered emphasising his physical suffering. God holds Him as He ascends, the dove of the Holy Spirit hovering over Them. At His feet is a crystal globe which represents the world of man which He saved by His sacrifice. Crystal objects were fairly common in Netherlandish paintings during this period. It was a sign of their innovation as well as their skill with oil based paints, enabling them to demonstrate their virtuosity.

Such a painting would encourage the supplicant, kneeling at the altar, to reflect on their relationship with the Trinity. In fact, as this altarpiece was destined for a Church adjacent to a hospital one could imagine a patient kneeling before this emotive masterpiece seeking divine intersession.

God is shown not as a wise old man but as the twin of Christ. This was a common device, especially in France dating back to the 13th century5, to emphasise that God was Christ’s Father and that man was created in His image. The background is beautiful and uplifting, representing the new dawn for those who follow Christ.

“I am come a light into the world, that whosoever believeth on me should not abide in darkness”6

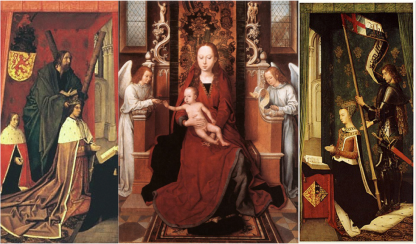

The Donor Panel

From all accounts this is a realistic portrait of Edward Bonkil who is believed to have commissioned van der Goes. He was the Provost of the Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross7, Edinburgh, the intended home for the altarpiece. Additional, identification is derived from the Bonkil family coat of arms prominently displayed on the organ stool.

The prominence of the organ has oft been debated but it is believed that Bonkil donated such an instrument to the college in 1466/7. It has been posited that the inclusion of the organ was to flatter James III’s love of music. This has been challenged but it could have been included in reference to the image that this unpopular King wanted to project.

The Royal Panels

This is a ‘mock up’ of how the altarpiece would have looked when open. The illustration demonstrates how the figures of the monarchs would have related to the central panel8. The current consensus is that this panel would have been an enthroned Madonna with angels.

The likenesses of the monarchs have been verified with reference to other contemporary depictions. However, these portraits lack the clarity and realism of the outer panels. It is believed that they were copied from reference works or may have been painted by an assistant of van der Goes.

The King’s Panel

This crowded panel is full of political and nationalist symbolism. It depicts the aforementioned James III, kneeling at a prie dieu as if praying to the Madonna.

The child is the future James IV which provides the best dating evidence. He was born in 1473 and his brother, James Stewart Duke of Ross, in 1476. As the contemporary convention was for the artist to include all living and even dead children, it seems likely that the altarpiece can be dated to 1473 – 1476.

James IV is a key character, not only for the future of Scotland and England but ultimately the formation of a united kingdom. He would marry Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty. He was therefore not only Henry VIII’s brother-in-law but also uncle to Edward VI and Elizabeth I9. Unlike his Father, he was a successful monarch who united the clans; was excommunicated for pursuing war with England and after his death at Flodden Erasmus10 wrote his epitaph. He was considered a Renaissance man, founding the College of Surgeons, strengthening Scotland’s navy and speaking a number of languages including Gaelic. He, also, carried out experiments into the nature of language and studied alchemy.

Both monarchs are crowned and dressed in robes of state surrounded with the trapping of Scottish nationhood. In the King’s panel, the Lion Rampant is significantly reversed so that it faces the central panel. Behind James III is the figure of St Andrew the patron saint of Scotland with his cross, the satire, which would become Scotland’s national flag.

The Queen’s Panel

Finally, we have Queen Margaret, James III’s consort, mirroring her husband kneeling at a prie dieu before the Madonna. Her marriage played an important role in the formation of what is now recognised as Scotland, her dowry included both Orkney and Shetland.

As with the King’s Panel there is an emphasis on Scottish nationhood. Her coat of arms as a Princess of Denmark is incorporated with that of Scotland. The Lion Rampant faces the correct way toward the missing panel. Behind her is a curtain adorned with thistles, James III was the first king to adopt this as the national emblem.

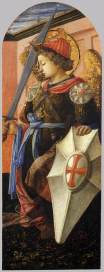

The consensus among art historians is that she is flanked by St George holding his red cross banner. However, given the tense relations between Scotland and England, it is unlikely that that the English patron saint would be included in such a Scottish altarpiece. Additionally, there is no evidence that Denmark, in general, and Queen Margaret, in particular, had any close facilitation with this saint. The Danish patron saint, adopted at this time, is Saint Canute or Knud II.

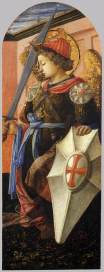

However, St Michael is frequently depicted in armour with a red Trinity Cross which would link back to the outer panel; these examples are by Lippi11 and Gerard David12. As the patron saint of the sick against evil, St Michael would have been an appropriate choice for a church adjacent to a hospital. This saint’s inclusion in this panel will be discussed in detail later in this paper.

Religious/Political Background

Before considering why these panels would have survived the mid 15th century iconoclasm a brief review of the Scottish Reformation is needed to provide some context.

The Scottish reformation was, by and large, based on John Knox’s Calvinism. This promoted the primacy of ‘The Word of God’ and the suffering of Christ for man’s sins. Thereby, dispensing with the need for any mediator other then Him so there is no place for priests, bishops or devotional objects including statues of the saints and altarpieces. In fact, these objects were deemed dangerous as they may lead the sinner into worshiping the object itself and thereby breaking the second commandment:

“Turn ye not unto idols, nor make yourselves molten gods: I am the Lord your God”13

This Scottish reformation had a significant political aspect which explains the support from the aristocracy and landowners. They blamed the country’s weakness and difficulties on a succession of Catholic, child monarchs with foreign female regents. In fact, during his first meeting with Calvin John Knox asked him four questions on whether a child monarch should be obeyed; whether a woman could govern “by divine law”; the third and fourth questions were the crux of the matter:

“whether it was necessary to obey a magistrate who enforces idolatry and condemns the true religion?….. [and] to which party ought godly men to adhere if devout men of position resist an idolatrous king by war”14.

Calvinism was particularly attractive as he separated the role of monarch from the individual. In addition, the emerging religion was communicated in the language of the people – Scots. This strengthened the perception of the reformed Church as a National institution15.

“In Scotland the unyielding reformers delivered themselves from the dregs of popery in a characteristically sweeping manner, offering an example of iconoclasm quite exceptional in its thoroughness”16

Vigilance against such idolatry is still predominant in The Church of Scotland and therefore continues to influence architecture and interior decor. This is typical a interior of today’s Kirk17, note the lack of altar and the prominence of the pulpit from where ‘The Word’ is preached.

Central Panel

Before considering the surviving panels through a Knox prism, one question must be explored further. Why did the central panel fail to survive?

18

18

There is no evidence of what the central panel looked like. The fact that the king, queen and lion rampant are facing the centre is suggestive of its existence. Art historians, including Panofsky, appear to have come to a consensus that the central panel was an enthroned Madonna with Angels a pattern which was utilised by van der Goes’ contemporaries include van Eyck and Memling.

Such subject matter was a focus for the iconoclasts’ wrath especially when included in an altarpiece which was the focal point for the despised Catholic mass. As early as the 1533 Lord Ochiltree19 decapitated a statute of the Virgin Mary. As well as representing a redundant mediator and object of veneration, the image of the Madonna was wrapped up in superstition and belief in witchcraft prevalent in Scotland at this time. Therefore, such images and objects received ritual hangings and burnings. This harked back to pre-Christian beliefs that to this day have resonance for many Scots. Additionally, Mary may have been viewed as a symbol for the mistrusted foreign female regents, all Mothers of Kings just like the Madonna.

The Trinity Panels Revisited

If the central panel failed to survive then why might the other panels ‘buck’ the trend? Revisiting the iconography of each of the panels in light of the developing religion may bear fruit. In this exercise it is not the original intentions of the Donor or painter that are important but how the elements were viewed by the contemporary viewer.

The Royal Panels

The surfeit of Scottish nationalist symbols would be attractive to a ruling class seeking to re-establish the position they believed their nation should hold on the European political stage. The use of the Lion Rampant, the patron saint of Scotland, the thistle, in addition, to the inclusion of key monarchs in the development of the country all serve to underline the nationalistic tone. As previously stated the Scottish Reformation was not purely a religious movement. The political element sought to rid the land of the corruption of the Roman Church and to see a King of the new religion on the throne to defend Scotland from foreign influence, not just from Rome but also France and, of course, the traditional enemy to the South.

With the central panel removed the King & the Queen appear to be kneeling before The Bible, before ‘The Word of God’. In fact, it looks as if St Andrew is instructing the King in the scriptures, thus the primacy of ‘The Word’ is prominent, in keeping with Calvinist beliefs.

What of St Michael? He is the Archangel depicted in art throughout the centuries as the leader of the celestial armies who defeat Satan. Given the upheaval of the mid 16th century this would have been an engaging allegory for the struggles to establish the reformed church. St Michael leads the armies of Calvinists against the evils of the Roman church enshrined in The Westminster Confession:

“He [the Pope of Rome] is Antichrist”20

21

21  22

22

St Michael’s holy day was not abolished until the 18th century. This day incorporated Scottish superstitions toward evil, when struans (or Stron bread) were traditionally baked in the shape of the Trinity Cross. ‘Struan’ means ‘small stream’ in the Gaelic. Many ancient magical wells were dedicated to St Michael when Christianity sought to replace the old beliefs. However, Scottish superstitions regarding the supernatural prevailed e.g. David I acknowledged these beliefs in law and James VI/I belief in witchcraft was so well known that Shakespeare included it in his Scottish play, ‘Macbeth’.

The royal panels also include a Danish princess and her coat of arms. The reformed churches of Scotland and Denmark not only recognised but also admired each other23.

The Donor Panel

This panel links the history of the Scottish monarchy to the reformers of St Andrews. Robert II was the founder of the Stewart dynasty and his Great Aunt by marriage was an ancestor of Edward Bonkil. While one of his descendents John Bonkil is recorded as a member of the St Andrews Kirk Session in 1569 24 and the ‘clerk-deputy’ of the city of St Andrews in 1573 25. It is unlikely that such family would have been unaware or kept a secret of their stellar lineage.

As for the inclusion of the angels – these did not offend the emerging doctrine. Their existence was never denied merely their ability to mediate on behalf of man.

All three panels appear be within the interior of the same church. A plain, stone building without adornment statutory or stain glass windows. It could be viewed as church cleansed of idolatry. This is in keeping with Calvin’s ideal that the beauty of God is not in the fabric of a building but in the worship of the people within it.

The Trinity Panel

The depiction of God is in strict violation of the tenets set out by Knox and such images were destroyed during the cleansing of the churches. However, as previously stated God is depicted as the twin of Christ. This common practise in France dating from the 13th century was based on the 110th Psalm:

“The Lord said unto my Lord,

Sit thou at my right hand,

Until make thine enemies thy footstool” 26

Although the Calvinists embraced the Psalms it is still unlikely that an image of God would pass the ‘graven idol’ test. The man behind Christ does not look like God merely someone lifting Christ to heaven, perhaps showing the soul departing the broken body.

The Christ figure is shockingly realistic, his suffering is clear for all to see and a key element for followers of Calvin & Knox. However, this panel still represents a fundamental weakness in the theory explored in this essay. Any depiction of the Trinity would be viewed as a devotional object and therefore would have been a target for those who took up the call to “…purge the kyrk of all kynd of monuments of idolatrye”27. Therefore, this panel’s survival may be attributed merely to the fact that it was on the reverse of King James III.

Conclusion

Waagen “recommended that art historians attend to politics, history, the character of the people, religious structures, customs, literature and the nature of the land in order to understand the artist…”28. Therefore, this paper is based on art historical theory, changing & developing religious doctrine, the political climate as well as the views and beliefs from contemporary Scottish society.

A classic iconographic approach would have sought the contemporary meaning(s) within the motifs depicted on the panels. Although, this has been identified as a weakness of Panofsky’s methodology, the quote on title page demonstrates that Panofsky was interested in the contemporary views as well as texts and traditions. The weakness in the pure iconographic approach, especially with Northern Renaissance art, is that it does not consider how such perceptions may change over time especially during periods of social, political, economic and religious turmoil. A great deal of art from this period was lost as a direct result of these changing perceptions.

Many art historians have commented on the ‘miraculous’ survival of Van der Goes’ ‘Trinity Panels’. This essay has attempted to demonstrate that the iconography of the survivors may have contributed to this ‘miracle’.

Post Script

One important historical fact has been ignored. During the ‘rough wooing’ of 1544 English forces commanded by Edward Seymour, the then Lord Hertford, sacked and looted both Edinburgh and Leith. However, the invaders did not lay siege to Edinburgh Castle keeping out of range of its cannon. As Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross was within this protective curtain it is unlikely that the painting was taken south at this time.

Endnotes

1 202 x 100.5 cm, oil on oak – on indefinite loan to the National Gallery of Scotland

2 Panofsky, quoted in Held, J S “Early Netherlandish Painting”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 37, No. 3 (September 1955), p212

3 They are next recorded in the possession of Queen Anne, Princess of Denmark, the consort of James VI/I in Oatlands Palace in 1617.

4 Blum, S N “Early Netherlandish Triptych”, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969, p 56.

5 Denny, D “The Trinity in Enguerrand Quarton’s Coronation of the Virgin”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 1 (March 1963), pp 48-52.

6 John 12:46

7 Founded by Margaret Guelders James III’s Mother/ and regent.

8 Hans Memling’s “Virgin & Child Enthroned with Two Angels”, 1485 – 1490, St Osyth’s Priory, St Osyth.

9 To many in England the Scottish claim to Elizabeth’s throne was stronger in light of whether she was considered illegitimate or not.

10 Teacher to James’ illegitimate son Alexander.

11 Filippo Lippi, “St Michael” c. 1456 – 58, Cleveland Museum of Art, USA.

12 “Altarpiece of St Michael”, late 15th Century, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

13 Leviticus 19:4

14 Eire, C M N “War Against Idols”, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989, p277.

15 The Scottish National Church was established in 1560.

16 Ashton, M “England’s Iconoclasts, Vol I”, Oxford: Clarendon, 1988, p60.

17 St James Parish Church, 1 Prestwick Road, Ayr.

18 Master of the St. Lucy Legend’s “Madonna and Child with Angels”, c. 1475 – 1483, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, USA.

19 The grandfather of the future and second Mrs John Knox.

20 Chapter 29 Section 2, The Westminster Confession, http://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/about_us/our_faith/westminster_confession_of_faith (viewed on 10 March 2013)

21 Archangel St Michael, Cathedral Cefalu, Sicily 12th Century.

22 Raphael, “St Michael Overwhelming the Demon”, c 1505, Louvre, Paris.

23 Donaldson, G “’The Example of Denmark’ in the Scottish Reformation” The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 27, No. 103 Pt. 1 (April 1948) p58-59.

24 University of Glasgow/University St Andrews: The Scottish History Society http://www.scottishhistorysociety.org/media/media_173536_en.pdf p323.

25 Archaeology Data Service http://www.ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/arch-352- 1/dissemination/pdf/vol_047/47_174_208.pdf p199.

26 Denny “The Trinity in Enguerrand Quarton’s Coronation of the Virgin”, p49

27 Fleming, D H “The Influence of the Reformation on Social and Cultural Life in Scotland’, The Scottish Historical Review Vol. 15, Bo. 57 (October 1917), p16.

28 Quoted in Belozerskaya, M “Burgundian Arts Across Europe”, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, p31

Tags: Iconoclasm; Scottish Reformation; Waagan; Bonkil; Knox; Calvin, iconographic; northern renaissance; Panofsky; Hugo van der Goes; van der Goes; Scotland, Scottish

Fig 2 (1910-11)

Fig 2 (1910-11)

Fig 11 (1911)

Fig 11 (1911)

Fig 14 “Terminator” 1984

Fig 14 “Terminator” 1984

Lightning (I lampi), 1909-10,

Lightning (I lampi), 1909-10,

From a distance the dominant colours are greens, greys and purples. However, as you move closer it is clear that:

From a distance the dominant colours are greens, greys and purples. However, as you move closer it is clear that: